DEFRA are running a consultation on the proposed amendments to The Heather and Grass etc. Burning (England) Regulations 2021 until 25th May 2025 – https://consult.defra.gov.uk/peatland-protection-team/heather-and-grass-burning-in-england/

Why moor heather burning is bad for our health

Anybody who lives on (or nearby) moorland will have experienced the smoke from winter heather burning.

Our heather moorlands were man made over the centuries by clearing trees and by grazing. This impoverished the soil encouraging mosses and heather to thrive. Latterly the need for heather for red grouse prompted the draining of peat bogs so that the heather could thrive even further. Unfortunately, peat bogs when drained start to dry out, oxidise, and emit large amounts of CO2 in the process. Fortunately, bog draining is being reversed in some areas in order to restore the health of peat bogs.

Why is it burned?

According to the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust’s Heather Burning page the main reasons are to provide new buds for red grouse to eat, suppress trees and to create firebreaks against wildfires.

What health impact does heather burning have?

Heather is a live plant and contains about 40% moisture.

A good comparison here is wood for wood-burners. This wood is considered “wet” if it contains more than 20% moisture. The government banned the sale of “wet” wood (on health grounds) in 2021 for phasing out completely by 2023.

Burning such “wet” woody matter releases significant amounts of particulate matter (PM) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) including benzo(a)pyrene (BAP) – a known carcinogen. According to DEFRA (Sources of PM 2.5s), exposure to PM increases the age-specific mortality risk, particularly from cardiovascular causes, and exposure to high concentrations of PM (e.g. during heather burns) can also exacerbate lung and heart conditions, significantly affecting quality of life, and increase deaths and hospital admissions.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) also say that epidemiological studies have shown that PAHs are associated with reduced lung function, exacerbation of asthma, and increased rates of obstructive lung diseases and cardiovascular diseases.

So, there is a clear link from reputable sources between smoke pollution and poor health.

The smoke from heather burning often follows the ground contours and descends into the valleys where the people live. Occasionally conditions have caused the smoke to reach Guisborough and Stokesley from the North York Moors affecting thousands of households beyond the National Park.

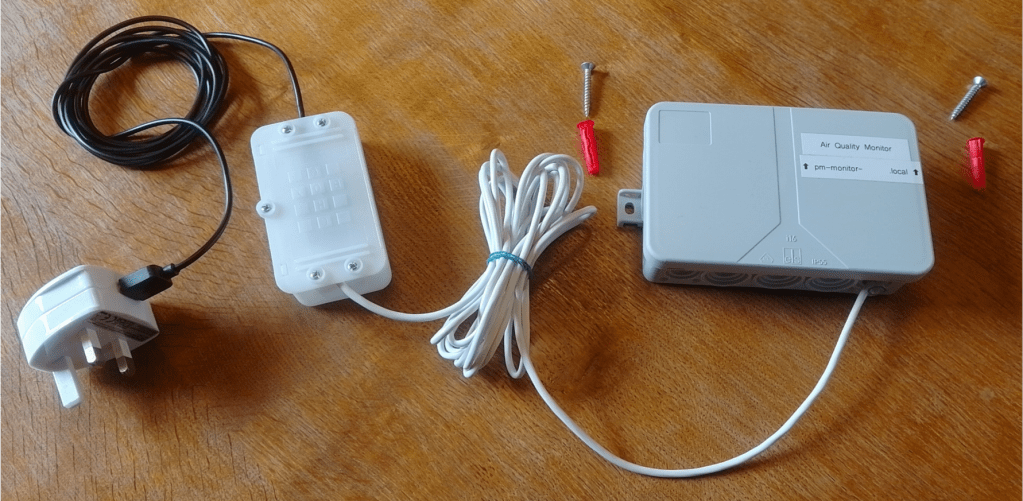

A member of Climate Action Stokesley and Village member has an air quality monitor on his house which frequently records >100μg/m3 during heather burns. The DEFRA guidance indicates this is “very high” and the WHO considers anything above 15μg/m3 to be a problem to health.

Mowing/cutting as an alternative to burning

Mowing does not contribute to air pollution and there is established research from the University of Leeds Ember project that shows burning has many adverse effects on the underlying peat and sphagnum moss. It increases the acidity of adjacent watercourses, reduces the water table in the underlying peat and reduces the macro-invertebrate population diversity.

Mowing will provide the necessary fire breaks to stop wildfires (the usual justification for burning).

British Moorland who manage 7 grouse moors in Scotland also advocate mowing over burning in a “narrow strip matrix” which provides far more metres of border between clearing and heather than burning. These borders provide cover for grouse chicks from winds and raptors.

They have found that tick infestation in chicks is significantly reduced by mowing along with other benefits.

Mowing also emits far less CO2 into the atmosphere and helps towards carbon reduction.

Now is the time for landowners, farmers and local communities to work together for a better future for all.

For details on air particulate monitoring across the North York Moors please see the Community Earth Project citizen science site at https://whitbyeskenergy.org.uk/emoncms/airquality/welcome (this project is based on a European citizen science project at https://sensor.community).

IUCN UK National Committee Burning on Peatland

Extract from: https://www.iucn-uk-peatlandprogramme.org/about-peatlands/peatland-damage/burning-peatlands

The topic of burning was a key consideration in the IUCN UK Peatland Programme (IUCN UK PP) Commission of Inquiry on Peatlands (Bain et al.,2011) and led to a summary briefing on Burning on Peatbogs (IUCN UK PP, 2011). A more recent IUCN UK PP publication, Briefing Note No. 8: Burning (Lindsay et al., 2014), summarised the scientific evidence from an ecological perspective. This followed Natural England’s Review of Upland Evidence NEER004 (2013) and Natural England’s Wildfire Evidence Review NEER014 (Glaves et al., 2020) on managed burning, and Peatbogs and Carbon (Lindsay, 2010). Our updated Position Statement (version 5) takes account of Natural England NEER155 (Noble et al., 2025). The Position Statement contains a full list of all the cited references. We recommend that readers looking to gain a broader understanding of the subject read a selection of these citations.

Key points:

- The overwhelming scientific evidence base finds that burning on peatlands causes damage to key peatland species, peatland ecosystem health, sustainability of peatland soils, and negative impacts on air and water quality.

- The majority of evidence finds no benefit to peatland ecosystem health in the UK from burning.

- Successful restoration of peatlands on hundreds of sites across the UK, without the use of fire, demonstrates that burning is not a necessary tool for peatland restoration. Burning is harmful to the prospects of the restoration of peat: repeated burning on already degraded areas further limits the growth of key peat forming species and hampers the recovery of the physical and hydrological properties of peat soils.

- Many plants are found within the peat matrix, but not all are able to create the conditions to form significant amounts of peat.

- In the context of a changing climate, the most effective long-term, sustainable solution for addressing increasing wildfire risk on peatlands is to return the sites to fully functioning bog habitat by removing those factors that can cause degradation, such as drainage, unsustainable livestock management and burning regimes. Despite a growing interest in using fire to reduce vegetation, there is currently no experimental field evidence from UK peatlands to suggest that burning is a valid wildfire management tool. Rewetting and restoring peatland will naturally, over time, remove the higher so-called ‘fuel load’ which arises from degraded peatland vegetation.

- Additional measures to control ignition risk and more effectively manage wildfire when it does occur will also be needed in tandem with any restoration action.